Greenpeace Makes Peace With Data Centres

Data centre operators should be more open about their energy use, according to Greenpeace

Environmental campaigner Greenpeace has called on data centres to be more open about energy use – and renewed its call for them to lead the way in using more renewable energy.

“ICT is crucial to tackling climate change,” said Tom Dowdall, climate and energy campaigner at Greenpeace. “We are not against data centres – we want them to lead the way to a green energy revolution.” Dowdall was speaking in a panel at the 451 Group’s Hosting and Cloud Transformation Summit in London, with a line-up of data centre efficency experts who expressed disappointment with Greenpeace’s campaign on data centre energy.

Which is best – efficiency or low-carbon?

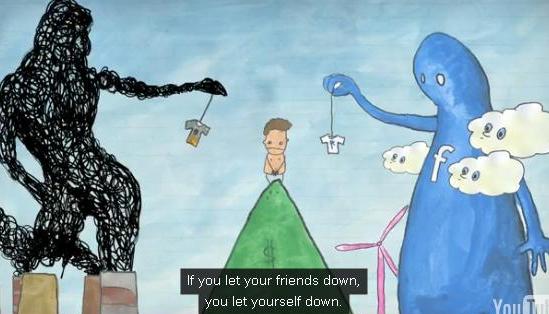

Greenpeace’s campaign against data centres’ use of carbon-intensive energy has centred on Facebook – which sited a data centre in Oregon, which gets most of its energy from coal – and on Apple – which recently launched a massive cloud service, without giving any details of its energy efficiency.

Greenpeace’s campaign against data centres’ use of carbon-intensive energy has centred on Facebook – which sited a data centre in Oregon, which gets most of its energy from coal – and on Apple – which recently launched a massive cloud service, without giving any details of its energy efficiency.

However, Facebook has defended the efficiency of its data centre, and also launched the Open Compute project to share its tips on how it got an enviably low Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE – the efficiency measure which divides the electricity used in the data centre, by the amount that reaches the IT racks).

The panel at HCTS argued that Greenpeace was hitting the wrong target, as data centres are more efficient than any other IT service, and are a core part of efficiency measures such as smart grids and smart transport systems designed to reduce other wastage of energy.

“The servers in data centres are on 24×7,” said Dr David Snelling of Fujitsu Laboratories, who is also vice chair of the EMEA technical work group for the Green Grid, “so most of the energy is spent in the use phase.” All servers have a certain embedded energy, used in their manfuacture and shipping, he explained. For servers outside data centres, this can be the main energy used by the servers, since they spend a lot of time idle.

“Cloud computing could cut the grid demand of servers in this country by 60 percent,” said Dr Ian Bitterlin of Ark Continuity, which runs an efficient (PUE 1.2) data centre in Wiltshire. Around 40 percent of Britain’s IT servers are being run in cabinets and old data centres, with a PUE of between three and seven or eight – which means up to 7W of electricity is being wasted for every Watt delivered to the servers – said Bitterlin.

Moving this IT to the cloud would shift it from inefficient servers to data centres running at a PUE of around 1.2.

Energy sources matter

Despite this, IT firms should also consider the source of their power, said Dowdall. Facebook uses Pacific Corp because its power is cheaper, but this has consequences beyond its carbon footprint: “Pacific is lobbying the government against clean air regulations,” said Dowdall, “and using Facebook’s money to do it.”

However, there is an economic imperative, said Andrew Lawrence, the 451’s research director for Eco-IT. “It is not just the energy cost,” said Lawrence. “There are grants and tax incentives as well.” Since Oregon has high unemployment and wants to attract industry, it is possible that locating in Oregon could have saved Facebook over $25 million (£16m), he said.

Greenpeace, too, has had to decide where to put its data, and has been revealed to be using a data centre service that relies heavily on coal power. Asked by eWEEK Europe about this, Dowdall admitted that it had been difficult to pin providers down since Greenpeace outsourced its IT.

Greenpeace now has a questionnaire it gives to hosting providers but most will not discuss their energy use, either with Greenpeace as a potential customer, or in order to provide information for the campaigner’s data centre report.

Most hosting companies regard their energy use as a commercial secret, which might give competitors an advantage, said Dowdall – although he could not see any particular danger in them revealing how much energy they use.

Snelling agreed. “It would have been nice to have this information published,” adding that most companies keep it secret.